library(tidyverse)4 Loops

4.1 Libraries and functions

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import random

import statistics

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from plotnine import *In the previous chapter, we learned how to sample random datasets from known distributions.

Here, we’ll combine that with a fundamental programming technique: loops.

4.2 Soft-coding parameters

Before we get onto loops, we have one quick detour to take.

In the last chapter, we “hard-coded” our parameters by putting them directly inside the rnorm or np.random.normal functions.

However, from here on, we will start “soft-coding” parameters or other values that we might want to change.

This is considered good programming practice. It’s also sometimes called “dynamic coding”.

n <- 100

mean_n <- 0

sd_n <- 1

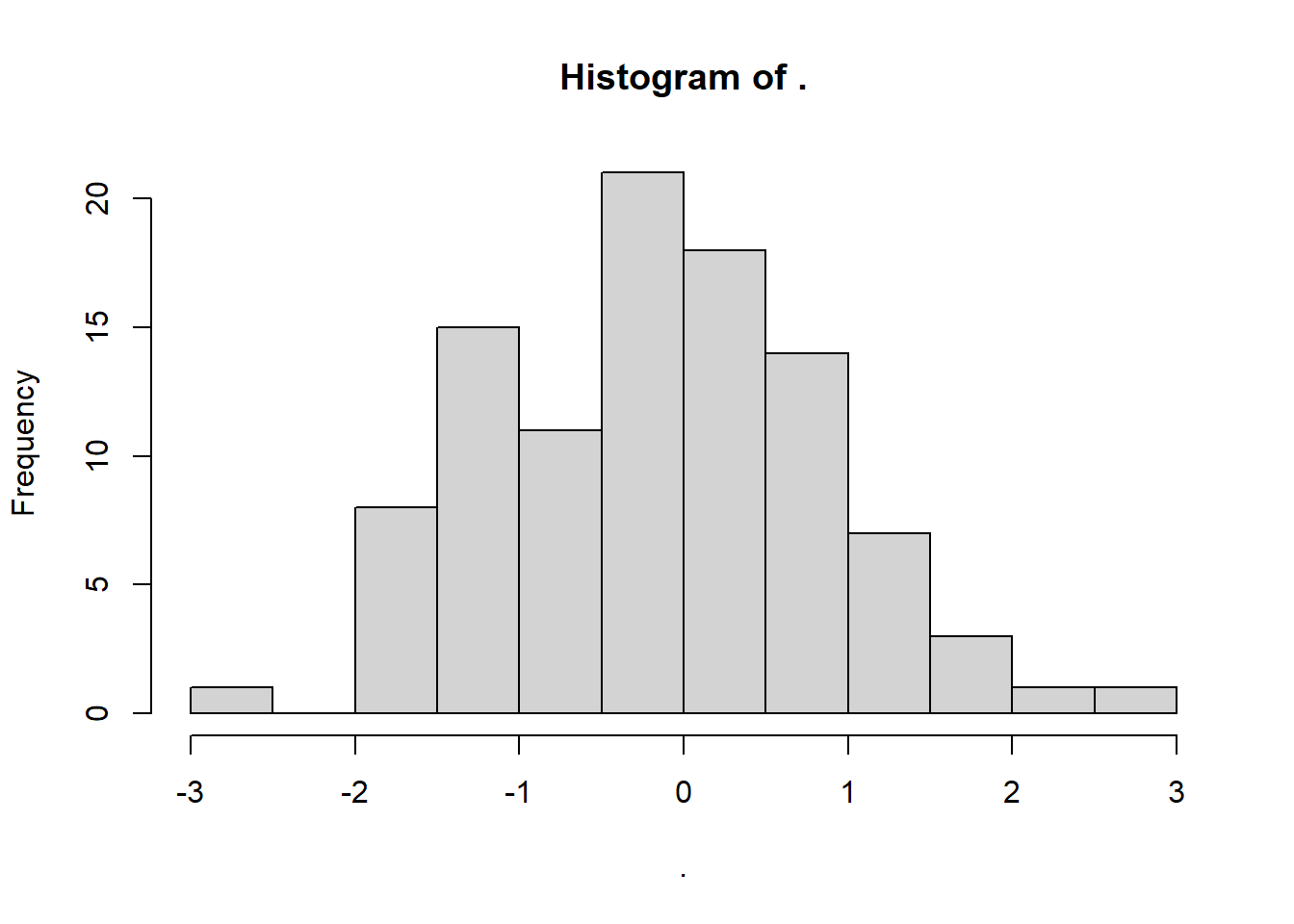

rnorm(n = n, mean = mean_n, sd = sd_n) %>%

hist()

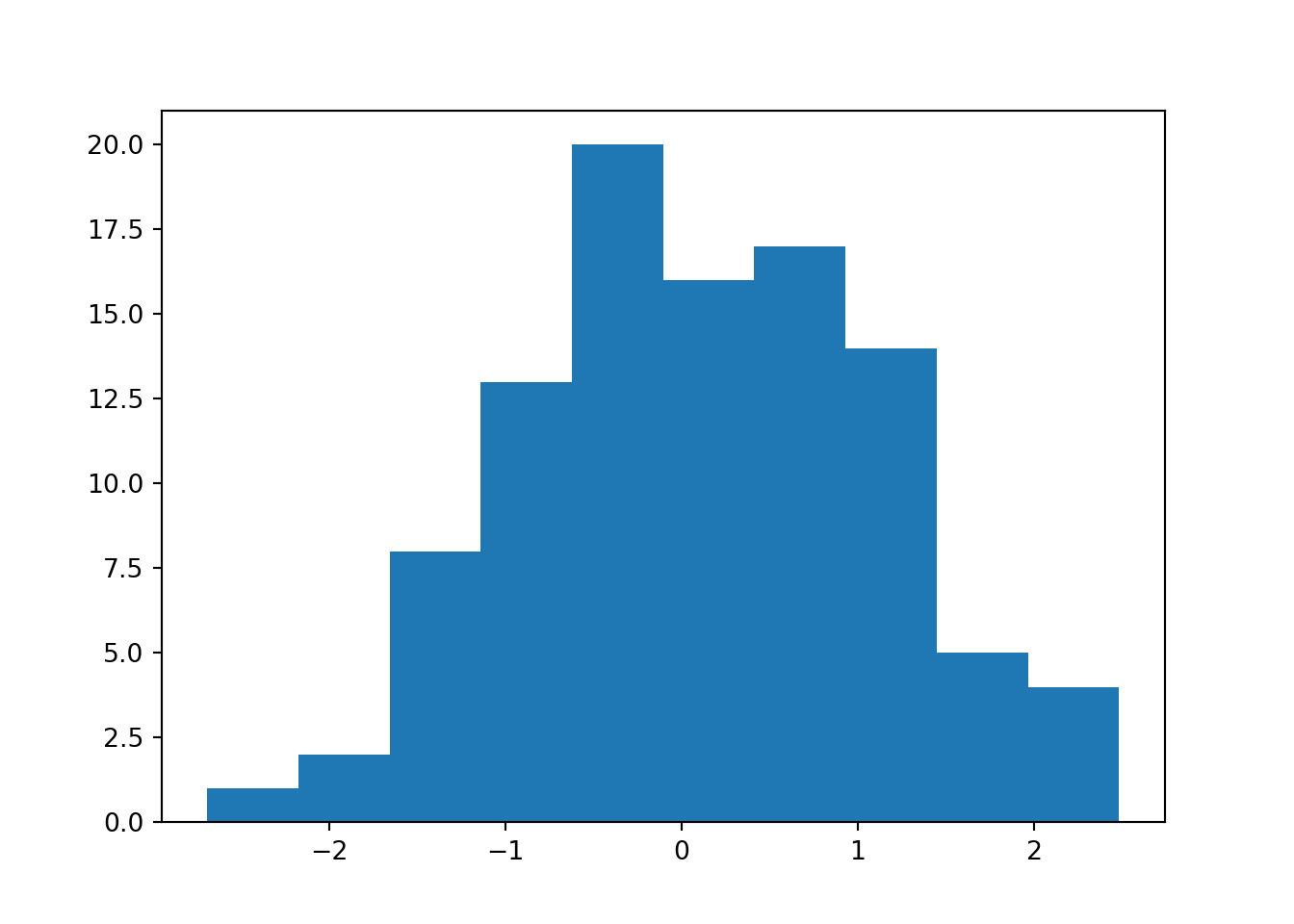

n = 100

mean = 0

sd = 1

plt.clf()

plt.hist(np.random.normal(loc = mean, scale = sd, size = n))

plt.show()

This might look like we’re writing out more code, but it will be helpful in more complex simulations where we use the same parameter more than once.

We’re also separating out the bits of the code that might need to be edited, which are all at the top where we can more easily see them, versus the bits we can leave untouched.

4.3 Loops

In programming, a loop is a chunk of code that is run repeatedly, until a certain condition is satisfied.

There are two broad types of loop: the for loop and the while loop. For the purposes of this course, we’ll only really worry about the for loop. For loops run for a pre-specified number of iterations before stopping.

4.3.1 For loop syntax

In R, the syntax for a for loop looks like this:

for (i in 1:5) {

print(i)

}[1] 1

[1] 2

[1] 3

[1] 4

[1] 5Here, i is our loop variable. It will take on the values in 1:5, one at a time.

For each value of our loop variable, the code inside the loop body - defined by {} curly brackets in R - will run.

for i in range(1, 6):

print(i)1

2

3

4

5Here, i is our loop variable. It will take on the values in 1:5, one at a time.

(Note that range(1, 6) does not include 6, the endpoint.)

For each value of our loop variable, the code inside the loop body - defined by indentation in Python - will run.

In this case, all we are asking our loop to do is print i. It’ll do this 5 times, increasing the value of i each time for each new iteration of the loop.

But, we can ask for more complex things than this on each iteration, and we don’t always have to interact with i.

4.3.2 Visualising means with for loops

You might’ve guessed based on context clues, but we can use for loops to perform repeated simulations using the same starting parameters (in fact, we’ll do that a lot in this course).

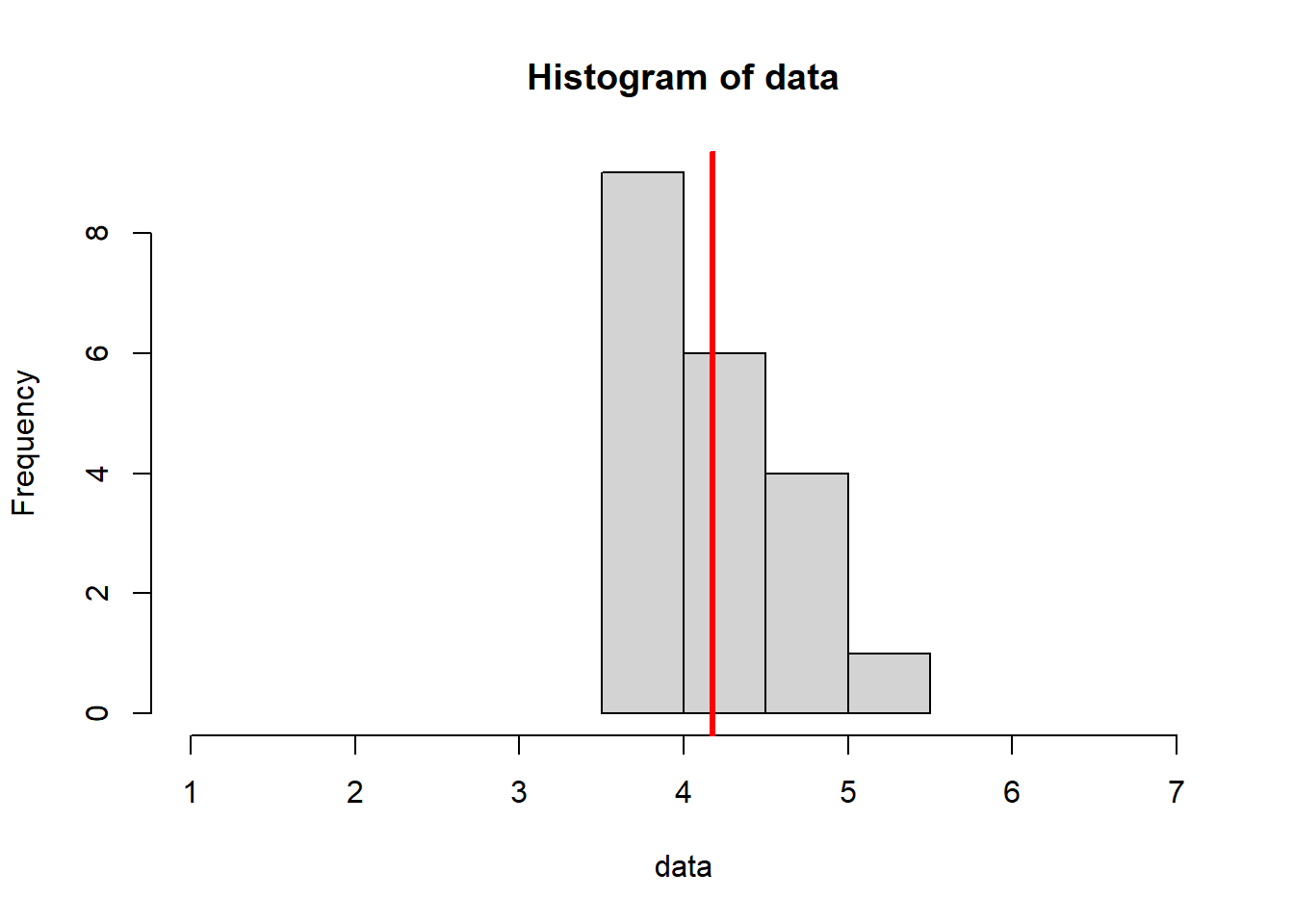

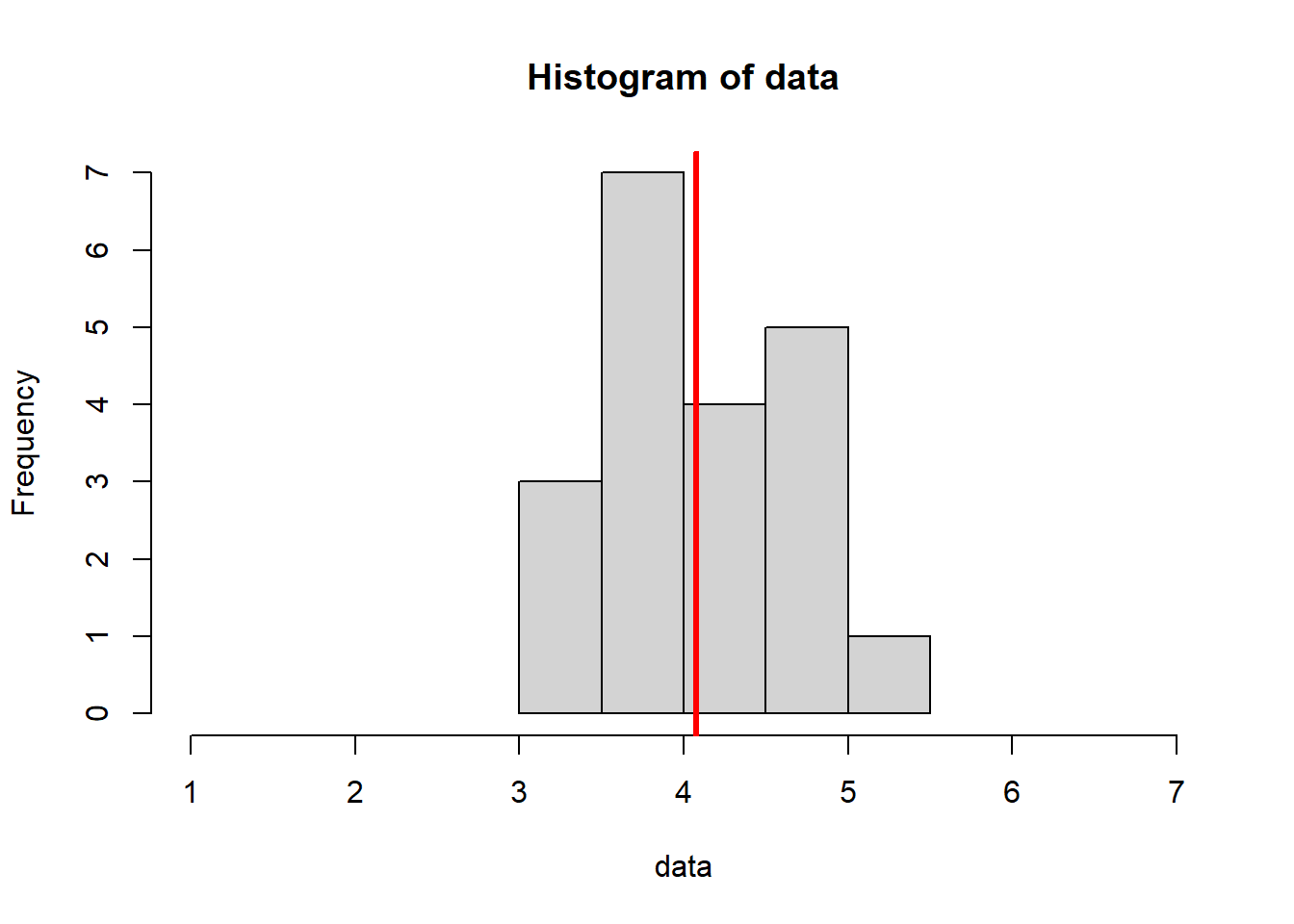

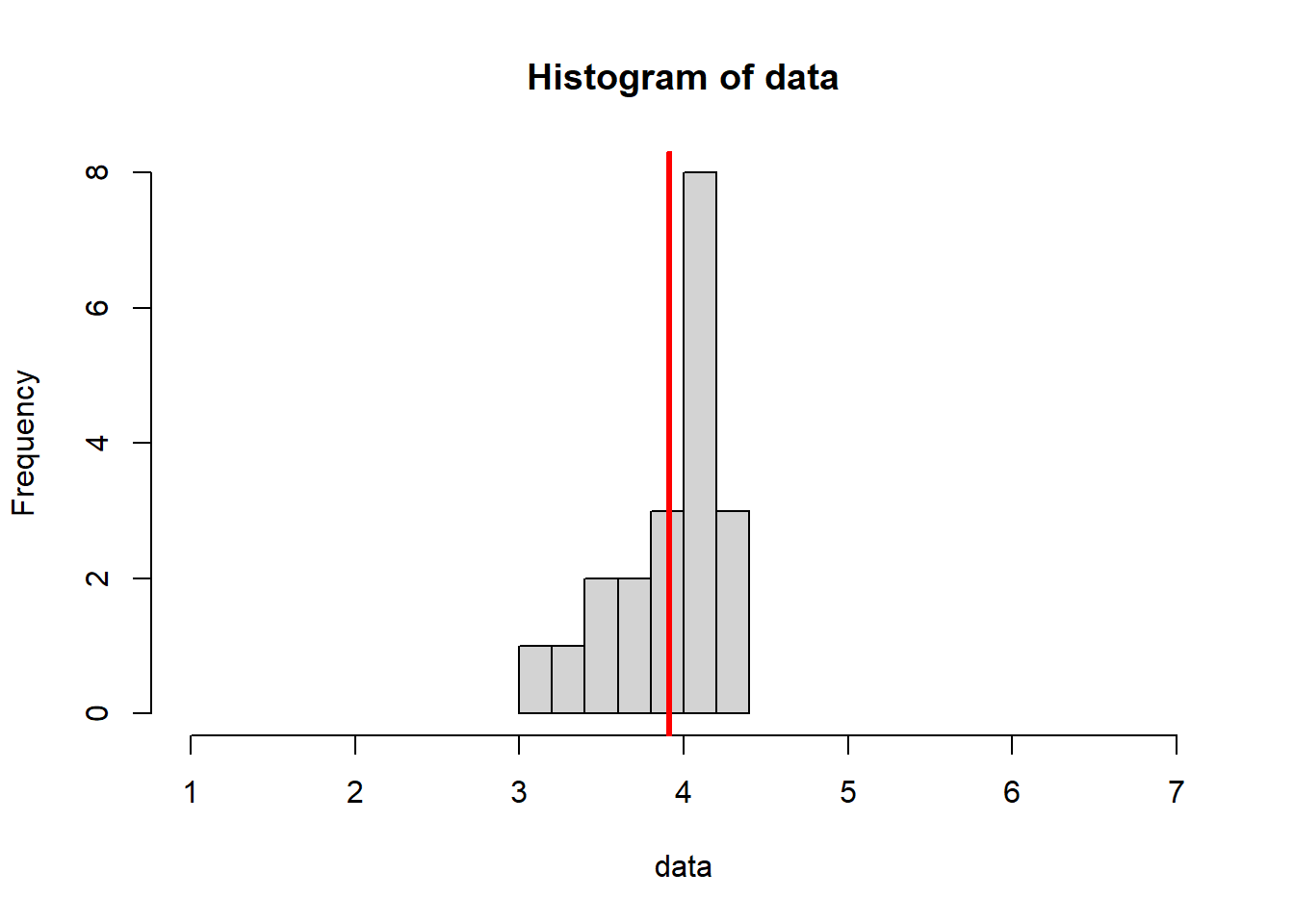

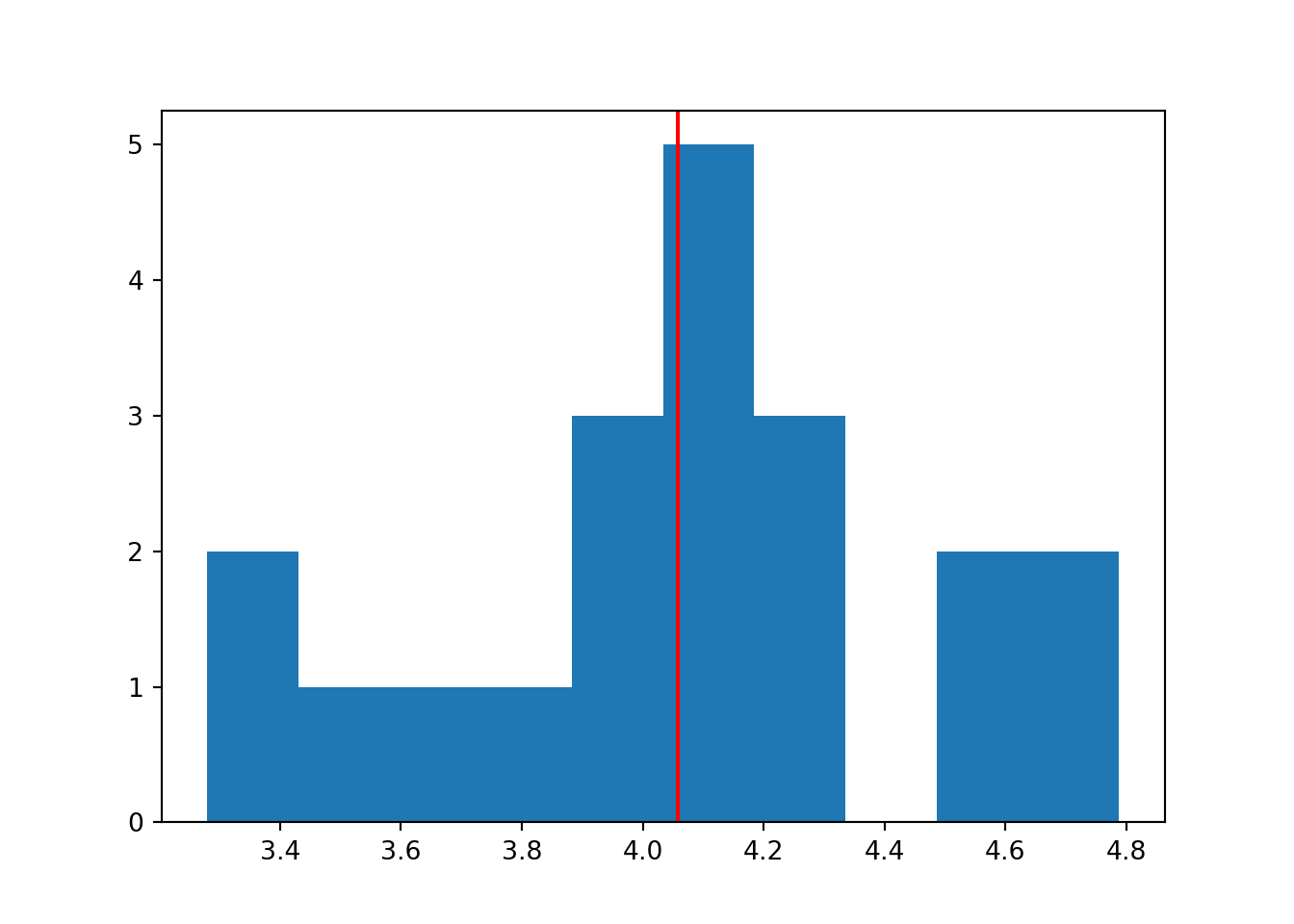

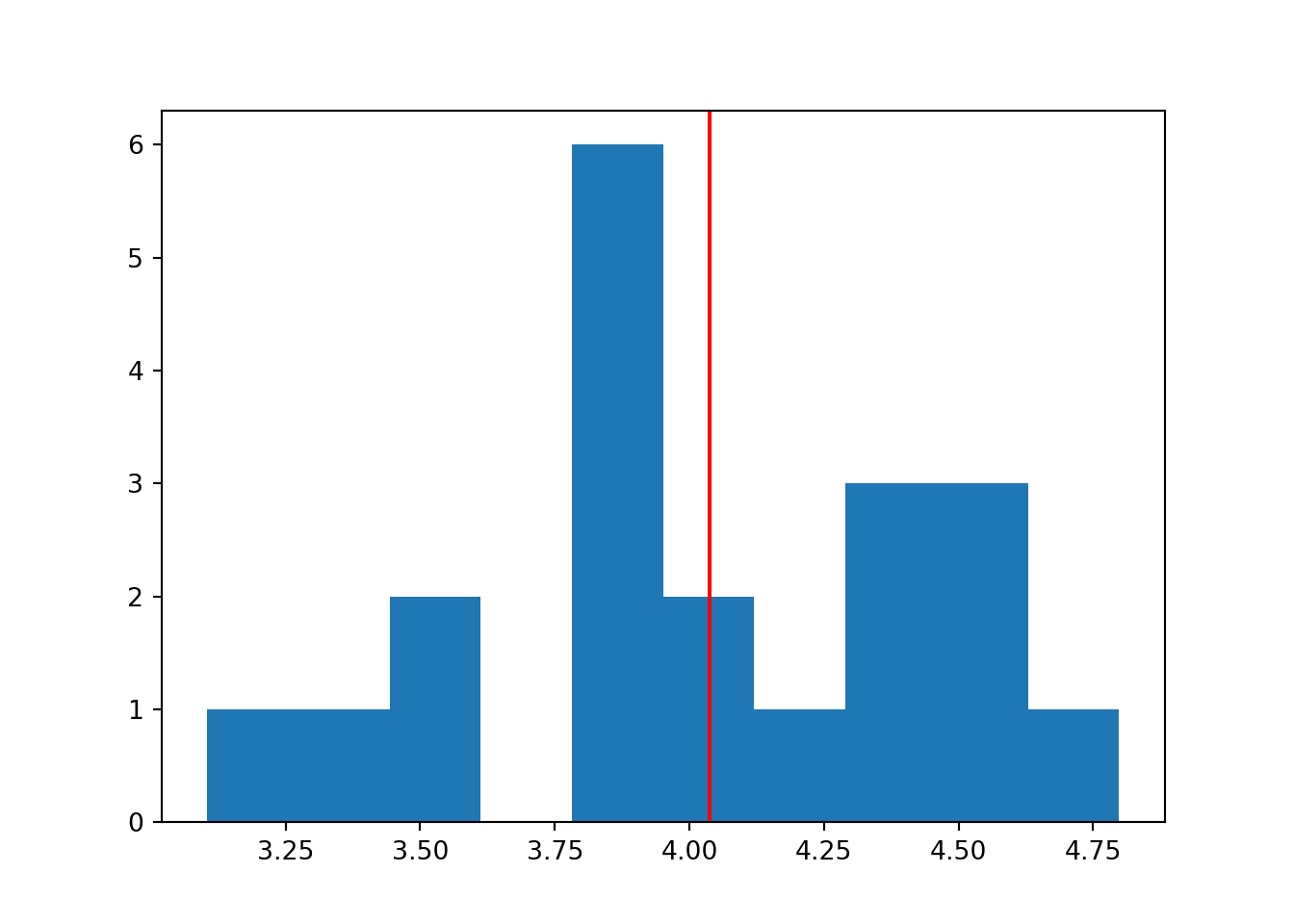

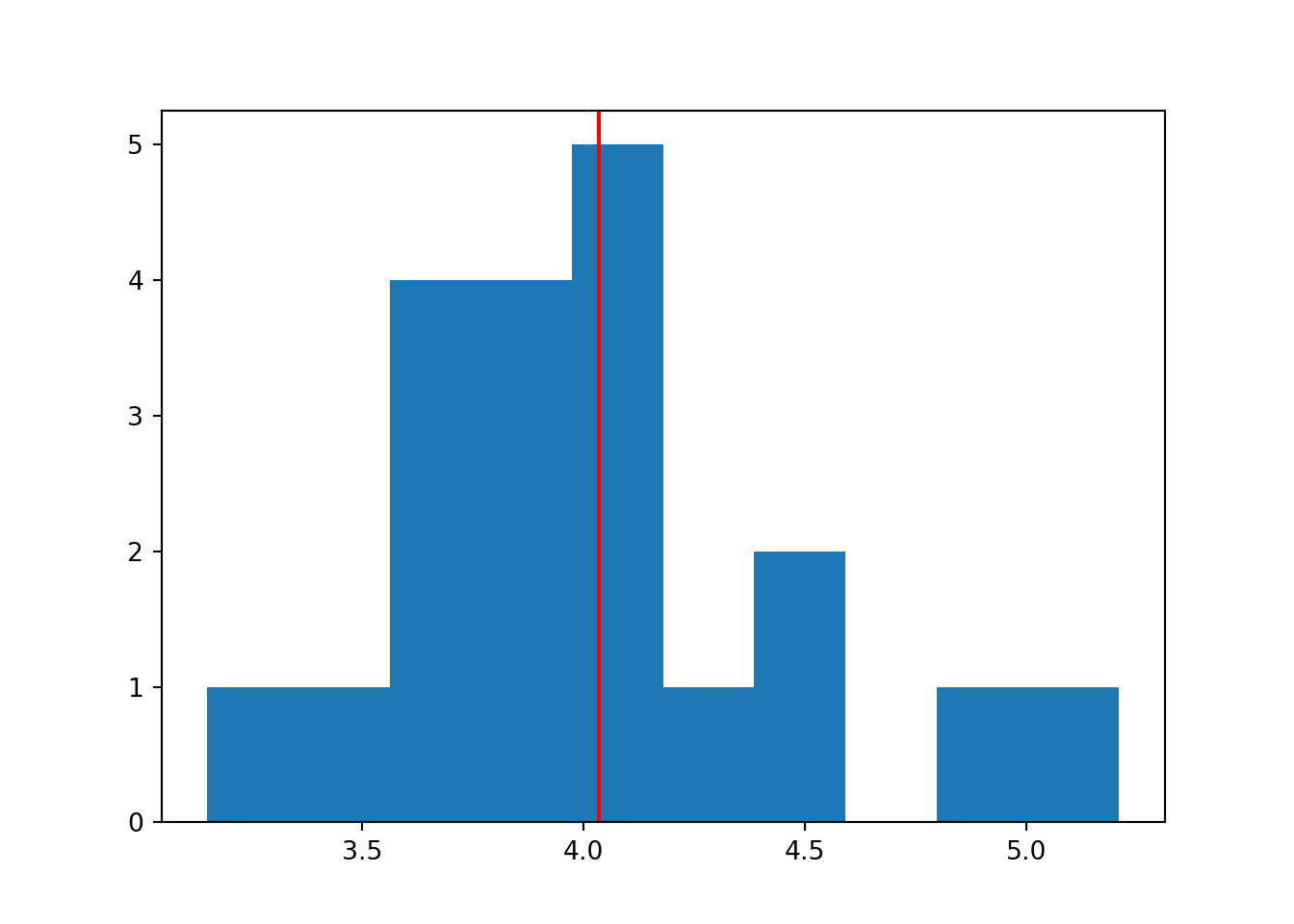

In this loop, we sample 3 unique datasets, each made up of 20 random data points, from a normal distribution with mean 4 and standard deviation 0.5.

Then, we produce a histogram for each dataset, overlaying the mean value each time.

for (i in 1:3) {

n <- 20

mean_n <- 4

sd_n <- 0.5

data <- rnorm(n, mean_n, sd_n)

hist(data, xlim = c(1, 7))

abline(v = mean(data), col = "red", lwd = 3)

}

plt.close()

for i in range(1, 4):

n = 20

mean = 4

sd = 0.5

data = np.random.normal(mean, sd, n)

plt.figure()

plt.hist(data)

plt.axvline(x = statistics.mean(data), color = 'r')

plt.show()

We can see that the means in each case are mostly hovering around 4, which is reassuring, since we know that’s the true population mean.

4.4 Exercises

4.4.1 Even numbers

4.4.2 Fizzbuzz

Let’s do something a little different, to really show the power of loops.

For some context, for those of you who’ve never played: Fizzbuzz is a silly parlour game that involves taking it in turns to count, adding 1 each time.

The trick is that all multiples of 3 must be replaced with the word “fizz”, and all multiples of 5 with the word “buzz” (and multiples of both with “fizzbuzz”).

4.5 Summary

This chapter covers some key coding practices that will be important later, including “soft-coding” of variables and for loops.

- Soft-coding, or dynamic coding, means assigning key parameters at the top of a script rather than within functions, so that they can more easily be changed later

- For loops in programming are chunks of code that are executed for a pre-specified number of iterations