# Load required R libraries

library(tidyverse)

library(ggResidpanel)

library(performance)

# Read in the required data

diabetes <- read_csv("data/diabetes.csv")

levers <- read_csv("data/levers.csv")

seeds <- read_csv("data/seeds.csv")11 Checking assumptions

- Know what statistical assumptions apply to logistic regression (and GLMs)

- Be able to evaluate whether a logistic regression meets the assumptions

11.1 Context

We can now assess the quality of a generalised linear model. Although we can relax certain assumptions compared to standard linear models (linearity, equality of variance of residuals, and normality of residuals), we cannot relax all of them - some key assumptions still exist. We discuss these below.

11.2 Section setup

We’ll use the following libraries and data:

# Load required Python libraries

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

from patsy import dmatrix

from scipy.stats import *

from plotnine import *

# Read in the required data

diabetes = pd.read_csv("data/diabetes.csv")

levers = pd.read_csv("data/levers.csv")

seeds = pd.read_csv("data/seeds.csv")11.3 Assumption checking

Below we go through the various assumptions we need to consider.

11.3.1 Assumption 1: Distribution of response variable

Although we don’t expect our response variable \(y\) to be continuous and normally distributed (as we did in linear modelling), we do still expect its distribution to come from the “exponential family” of distributions.

The exponential family

The exponential family contains the following distributions, among others:

- normal

- exponential

- Poisson

- Bernoulli

- binomial (for fixed number of trials)

- chi-squared

You can use a histogram to visualise the distribution of your response variable, but it is typically most useful just to think about the nature of your response variable. For instance, binary variables will follow a Bernoulli distribution, proportional variables follow a binomial distribution, and most count variables will follow a Poisson distribution.

If you have a very unusual variable that doesn’t follow one of these exponential family distributions, however, then a GLM will not be an appropriate choice. In other words, a GLM is not necessarily a magic fix!

11.3.2 Assumption 2: Correct link function

A closely-related assumption to assumption 1 above, is that we have chosen the correct link function for our model.

If we have done so, then there should be a linear relationship between our transformed model and our response variable; in other words, if we have chosen the right link function, then we have correctly “linearised” our model.

11.3.3 Assumption 3: Independence

We expect that the each observation or data point in our sample is independent of all the others. Specifically, we expect that our set of \(y\) response variables are independent of one another.

For this to be true, we have to make sure:

- that we aren’t treating technical replicates as true/biological replicates;

- that we don’t have observations/data points in our sample that are artificially similar to each other (compared to other data points);

- that we don’t have any nuisance/confounding variables that create “clusters” or hierarchy in our dataset;

- that we haven’t got repeated measures, i.e., multiple measurements/rows per individual in our sample

There is no diagnostic plot for assessing this assumption. To determine whether your data are independent, you need to understand your experimental design.

You might find this page useful if you’re looking for more information on what counts as truly independent data.

11.4 Other features to check

There are a handful of other features or qualities that can affect the quality of model fit, and therefore the quality of the inferences we draw from it.

These are not necessarily “formal” assumptions, but it’s good practice to check for them.

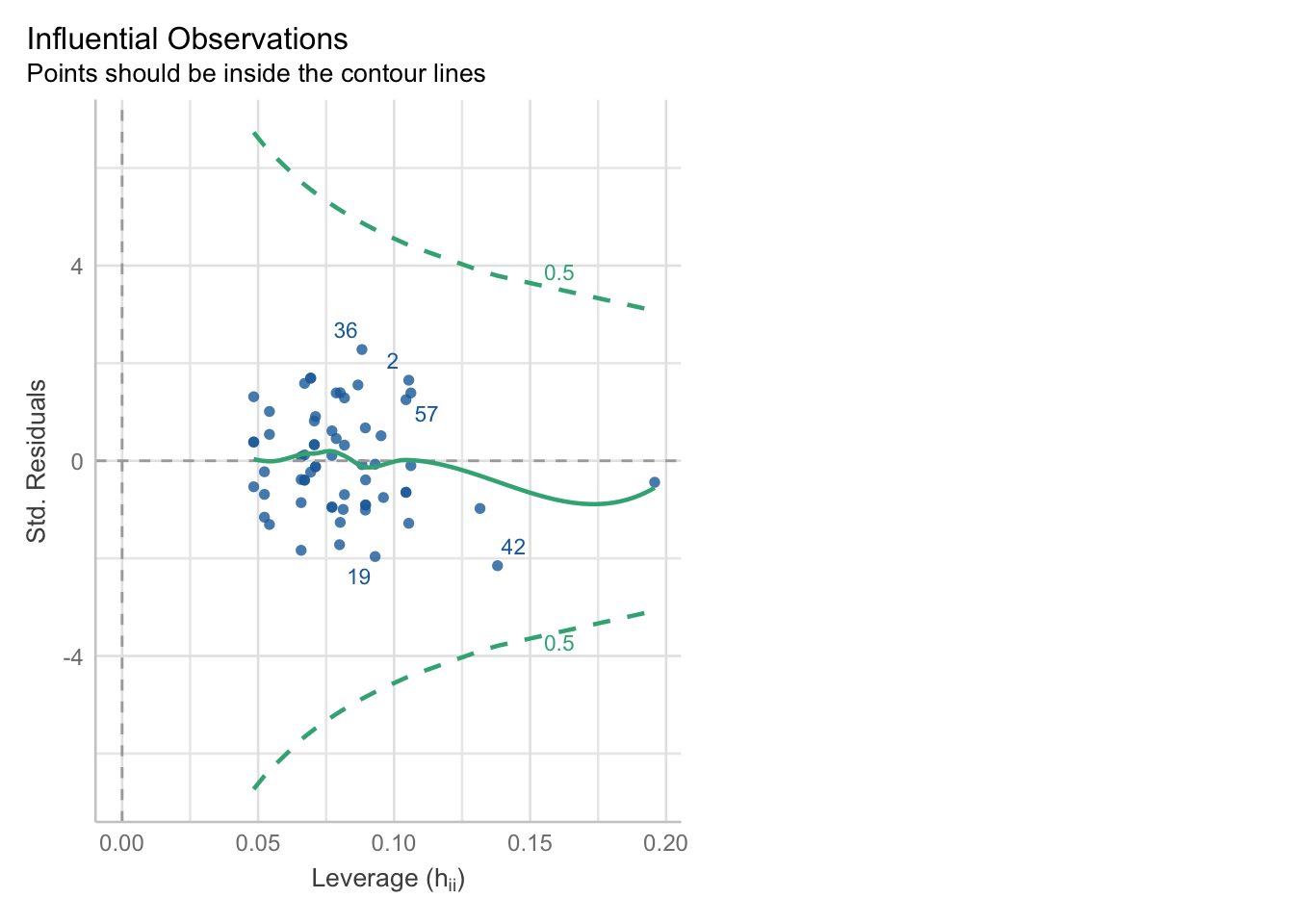

Lack of influential observations

A data point is overly influential, i.e., has high leverage, if removing that point from the dataset would cause large changes in the model coefficients. Data points with high leverage are typically those that don’t follow the same general “trend” as the rest of the data.

Lack of collinearity

Collinearity is when predictor variables are overly/strongly correlated with each other. This can make it very difficult to estimate the right beta coefficients and individual p-values for those predictors.

Dispersion

This is mentioned here for completeness, and as a bit of sizzle for next chapter when we talk about Poisson regression.

We won’t be worrying about dispersion in logistic regression specifically.

If you want more detail, you can skip ahead now to Section 12.7.

11.5 Assessing assumptions & quality

In linear modelling, we rely heavily on visuals to determine whether various assumptions were met.

When checking assumptions and assessing quality of fit for GLMs, we don’t use the panel of diagnostic plots that we used for linear models any more. However, there are some visualisations that can help us, plus several metrics we can calculate from our data or model.

| Is it a formal assumption? | How can I assess it? | |

|---|---|---|

Response variable comes from a distribution in the exponential family & The model uses the right link function |

Yes | Knowledge of the experimental design Some plots, e.g., posterior predictive check/uniform Q-Q, may help |

| Independent observations | Yes | Knowledge of experimental design There are no formal tests or plots that assess independence reliably |

| Influential observations | No | Cook’s distance/leverage plot |

| Lack of collinearity | No | Variance inflation factor |

| Dispersion | Sort of | Calculating the dispersion parameter Can also be visualised |

diabetes <- read_csv("data/diabetes.csv")

glm_dia <- glm(test_result ~ glucose * diastolic,

family = "binomial",

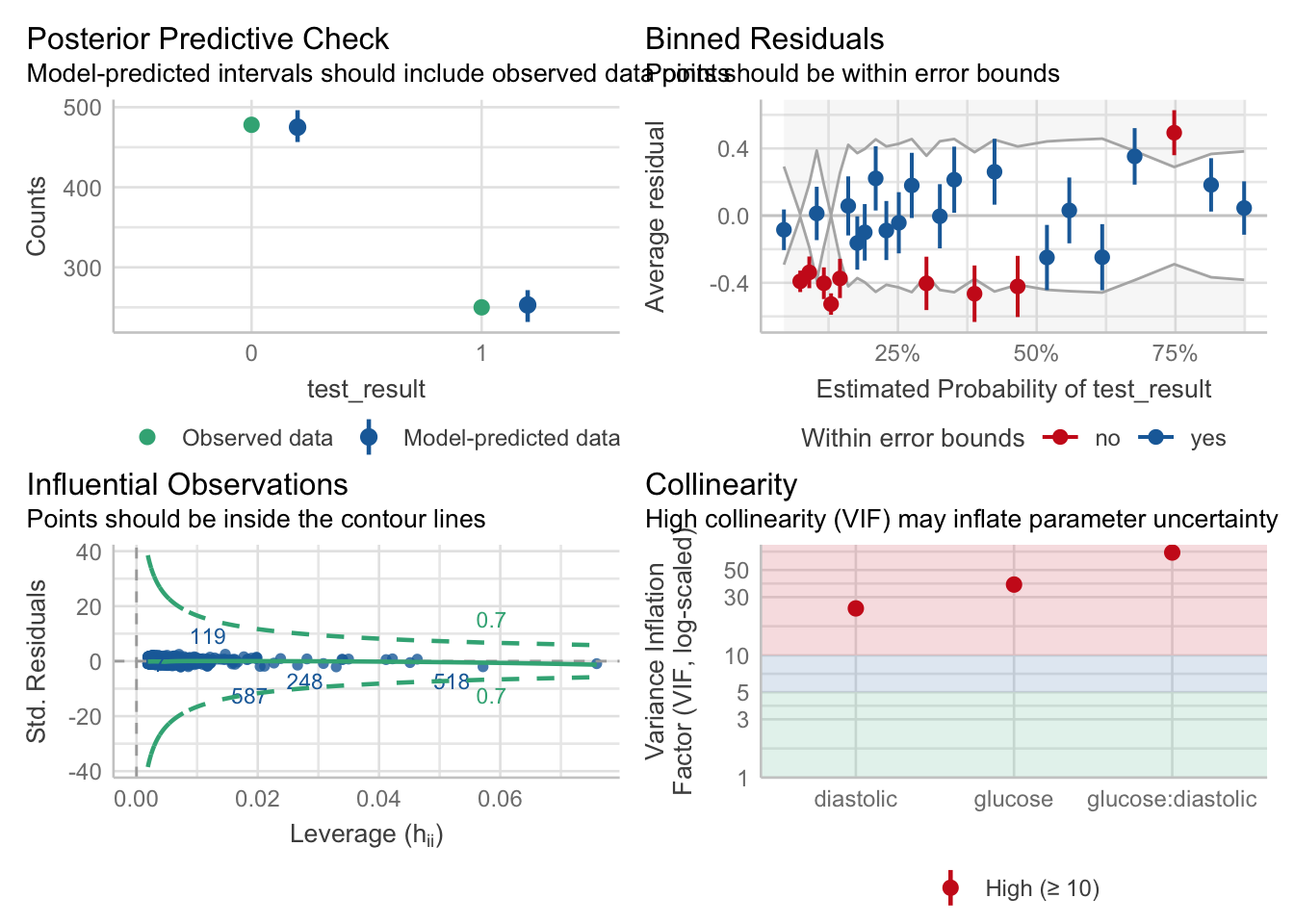

data = diabetes)Let’s fit some useful diagnostic plots, using the diabetes and aphids example datasets.

We’re going to rely heavily on the performance package in R for assessing the assumptions and fit of our model.

The check_model function will be our primary workhorse. This function automatically detects the type of model you give it, and produces the appropriate panel of plots all by itself. (So, so cool. And yes, it works for linear models too!)

Creating diagnostic plots in Python is not straightforward, since there are no decent packages out there. However, that does not mean we can’t check assumptions! In the next few sections we’ll visit every assumption individually using code.

If you’re interested in the visual aspect, just look at the R code.

We’ll start with creating the model.

diabetes_py = pd.read_csv("data/diabetes.csv")

model = smf.glm(formula = "test_result ~ glucose * diastolic",

family = sm.families.Binomial(),

data = diabetes_py)

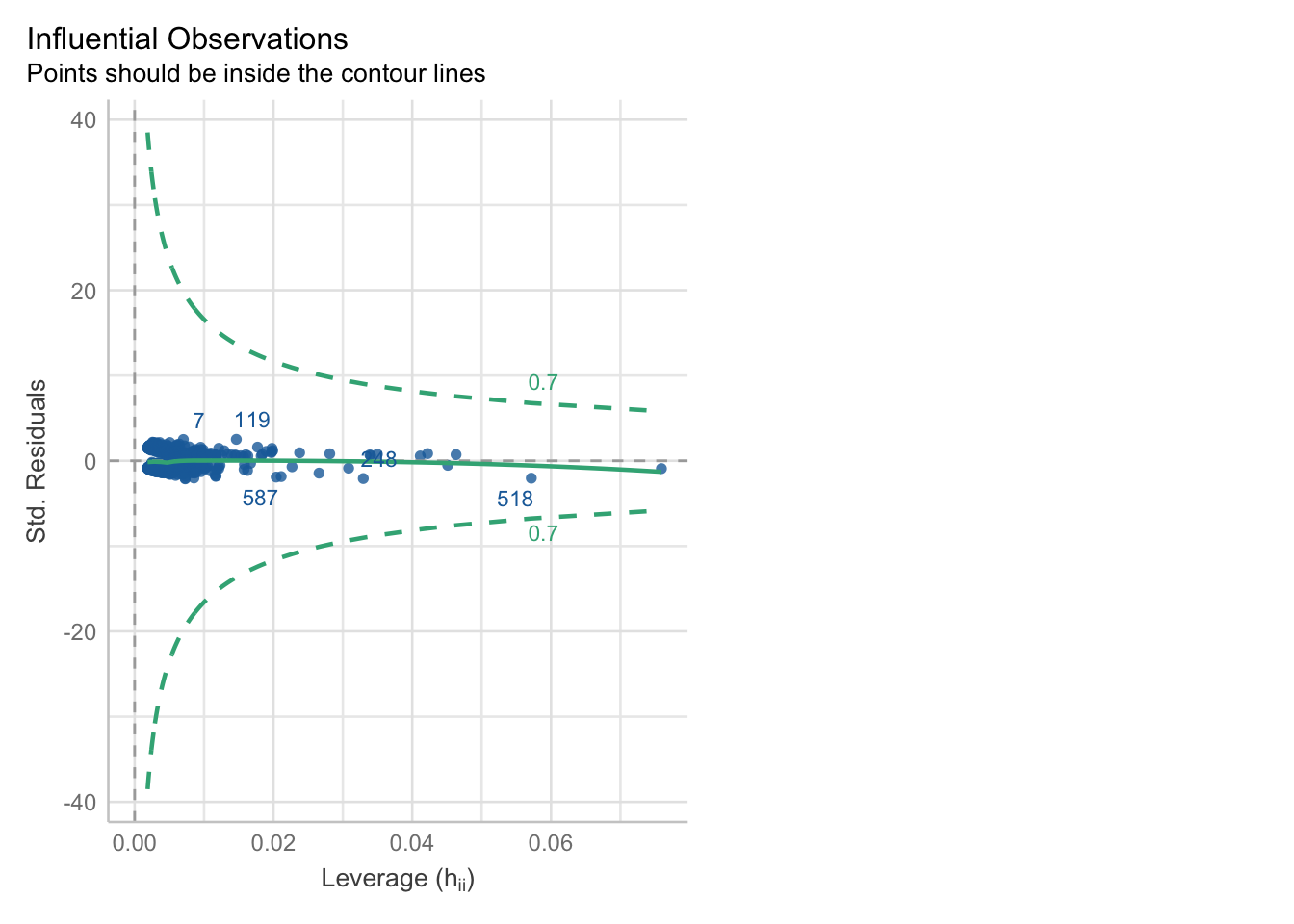

glm_dia_py = model.fit()11.5.1 Influential observations

We can check for outliers via a leverage plot (in performance), which you may remember from linear modelling.

Ideally, data points would fall inside the green contour lines. Data points that don’t will be highlighted in red.

check_model(glm_dia, check = 'outliers')Cannot simulate residuals for models of class `glm`. Please try

`check_model(..., residual_type = "normal")` instead.Alternatively, we can use the check_outliers function:

check_outliers(glm_dia, threshold = list('cook' = 0.5))OK: No outliers detected.

- Based on the following method and threshold: cook (0.5).

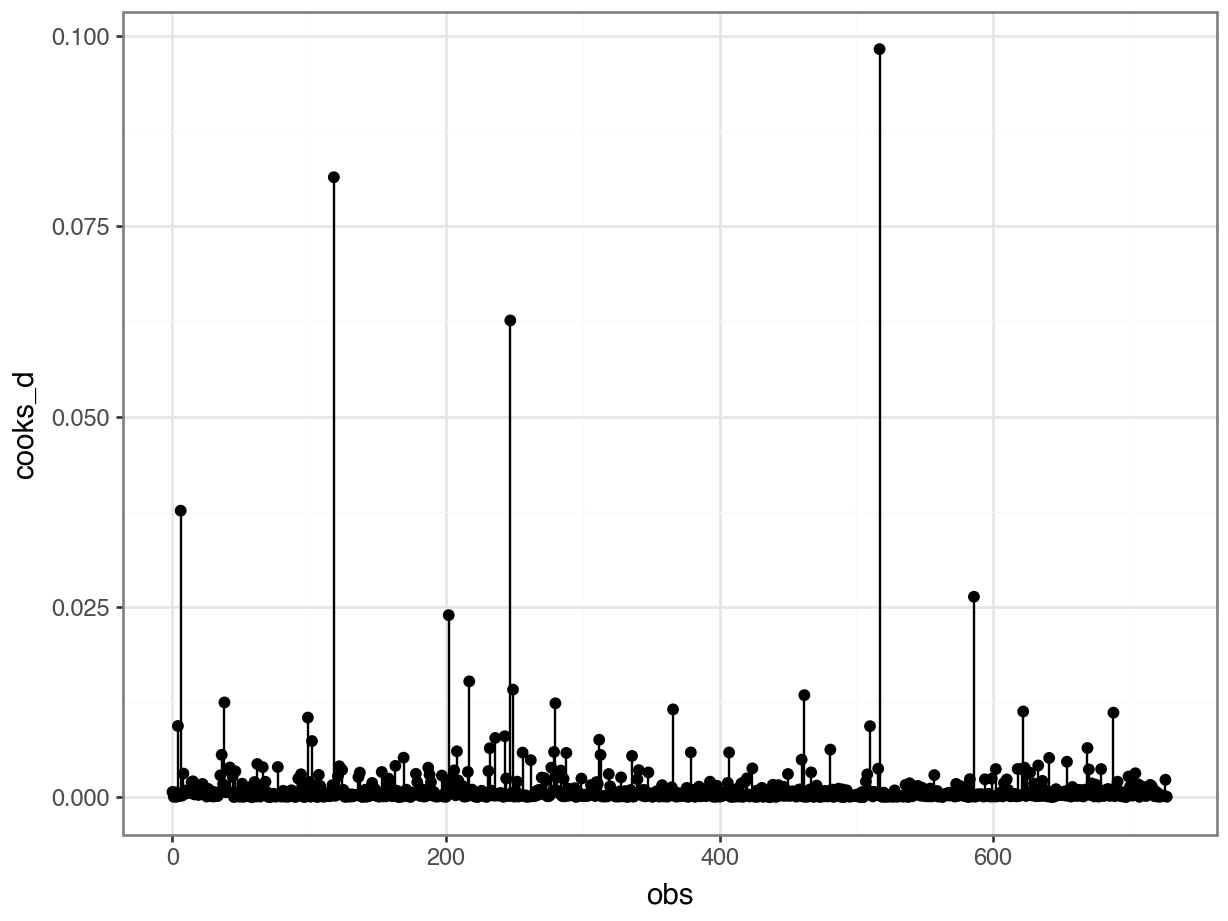

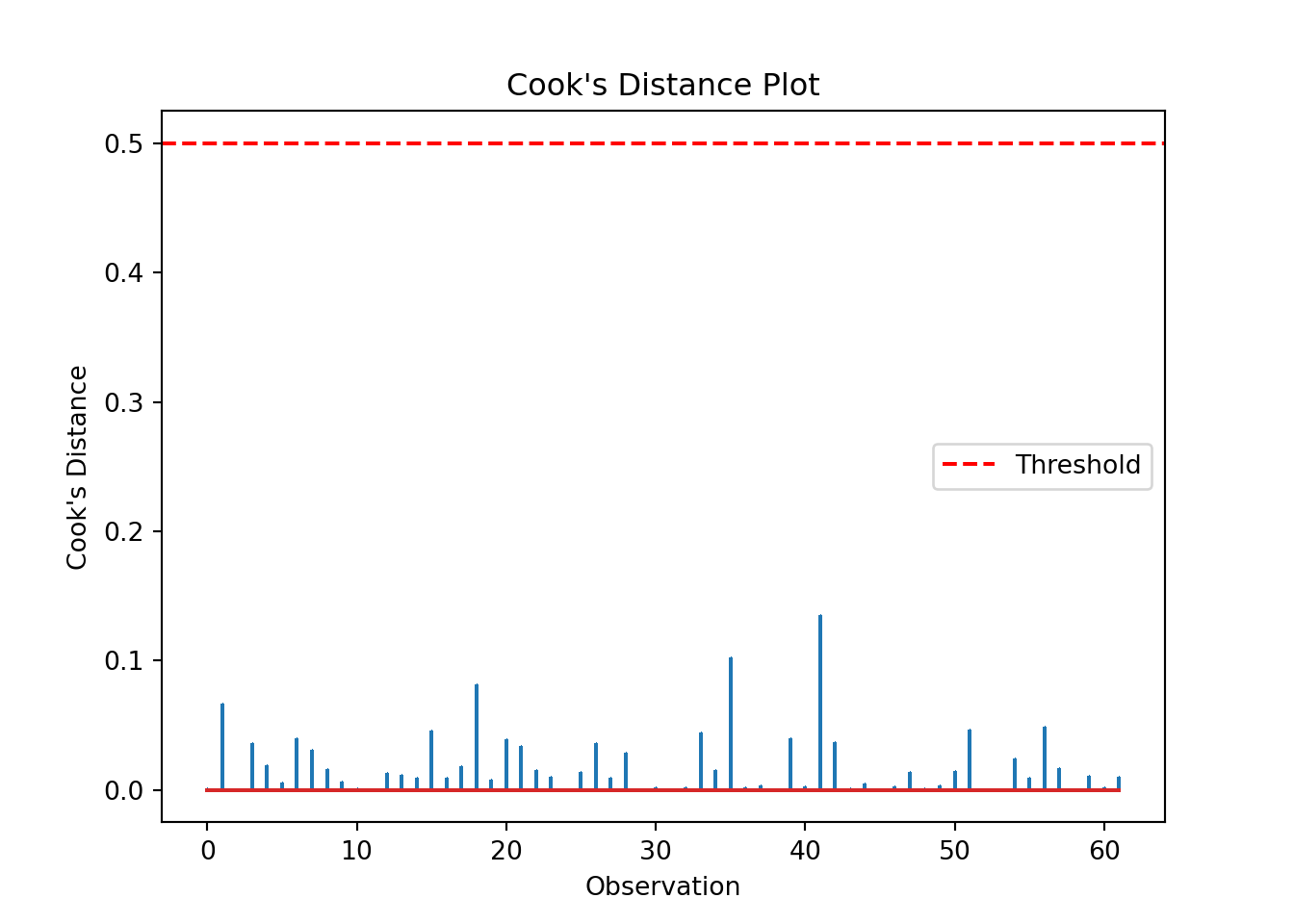

- For variable: (Whole model)That said, this is the one plot we can create quite easily: Cook’s D.

We can use the get_influence function to extract information like leverage, Cook’s distance etc. about all of our data points:

# extract the Cook's distances

glm_dia_py_resid = pd.DataFrame(glm_dia_py.

get_influence().

summary_frame()["cooks_d"])

# add row index

glm_dia_py_resid['obs'] = glm_dia_py_resid.reset_index().indexWe now have two columns:

glm_dia_py_resid.head() cooks_d obs

0 0.000709 0

1 0.000069 1

2 0.000641 2

3 0.000080 3

4 0.009373 4We can use these to create the plot:

p = (ggplot(glm_dia_py_resid,

aes(x = "obs",

y = "cooks_d")) +

geom_segment(aes(x = "obs", y = "cooks_d", xend = "obs", yend = 0)) +

geom_point())

p.show()matplotlib

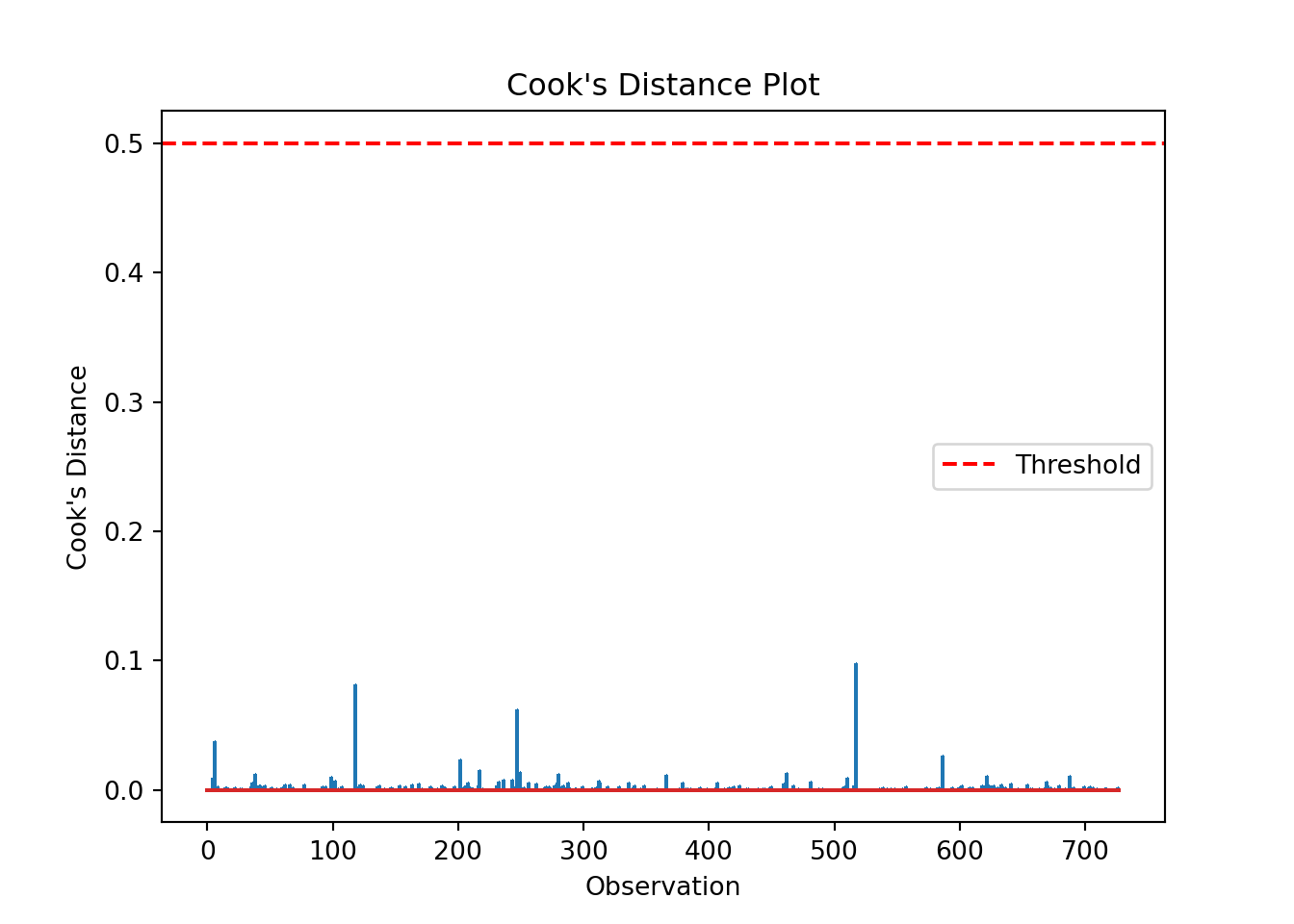

influence = glm_dia_py.get_influence()Then, we can visualise and interrogate that information.

We can produce a Cook’s distance plot (this uses matplotlib):

cooks = influence.cooks_distance[0]

plt.stem(np.arange(len(cooks)), cooks, markerfmt=",")

plt.axhline(0.5, color='red', linestyle='--', label='Threshold')

plt.xlabel('Observation')

plt.ylabel("Cook's Distance")

plt.title("Cook's Distance Plot")

plt.legend()

plt.show()and/or we can extract a list of data points with a Cook’s distance greater than some specified threshold:

influential_points = np.where(cooks > 0.5)[0] # Set appropriate threshold here

print("Influential points:", influential_points)Influential points: []The list is empty, indicating no high leverage points that we need to worry about.

We can check which points may be influential, for example by setting a threshold of > 0.5:

influential_points = glm_dia_py_resid[glm_dia_py_resid["cooks_d"] > 0.5]

print("Influential points:", influential_points)Influential points: Empty DataFrame

Columns: [cooks_d, obs]

Index: []The DataFrame is empty, indicating no high leverage points that we need to worry about.

Remember:

- Outliers and influential points aren’t necessarily the same thing; all outliers need to be followed up, to check if they are influential in a problematic way

- You can’t just drop data points because they are inconvenient! This is cherry-picking, and it can impact the quality and generalisability of your conclusions

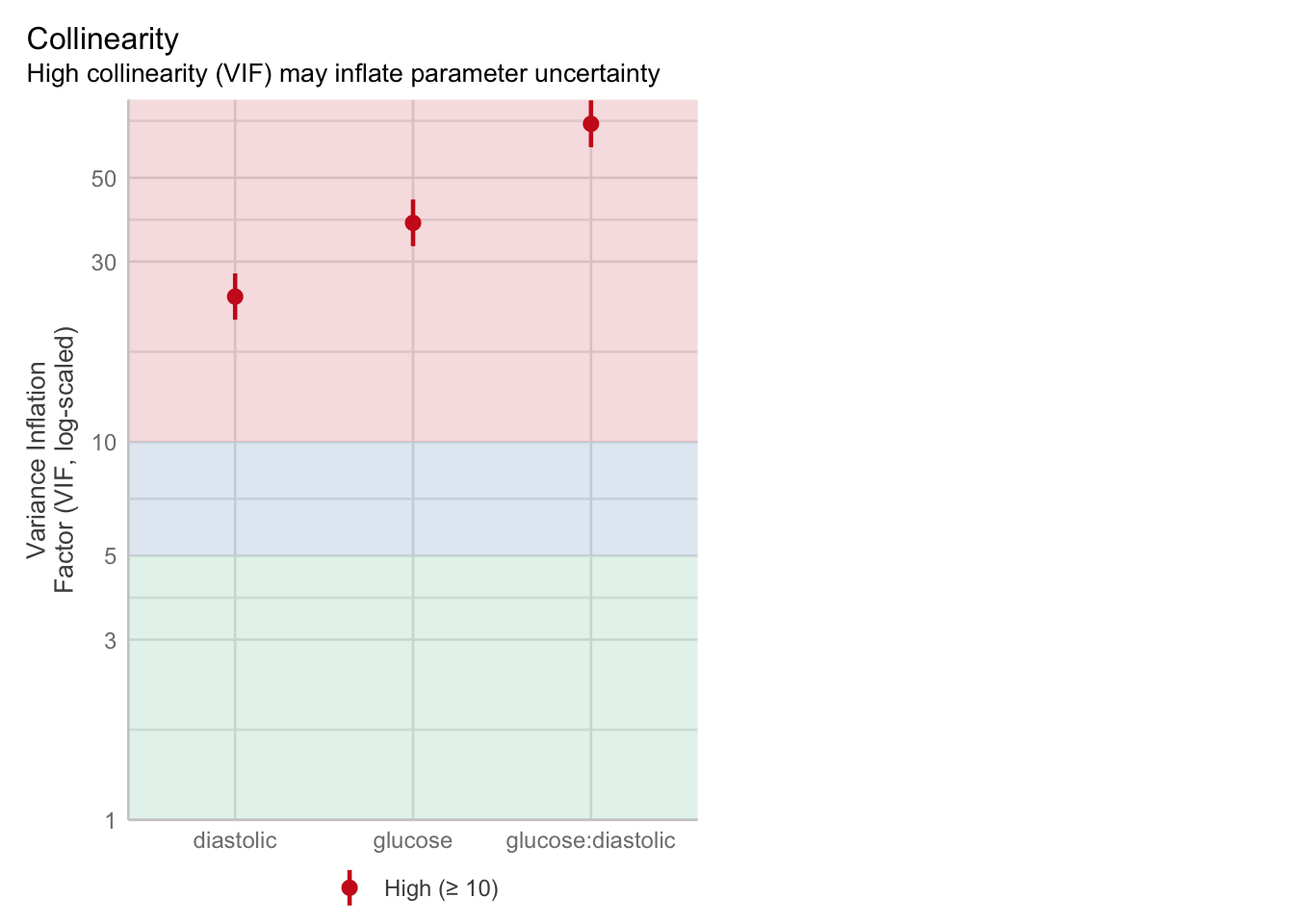

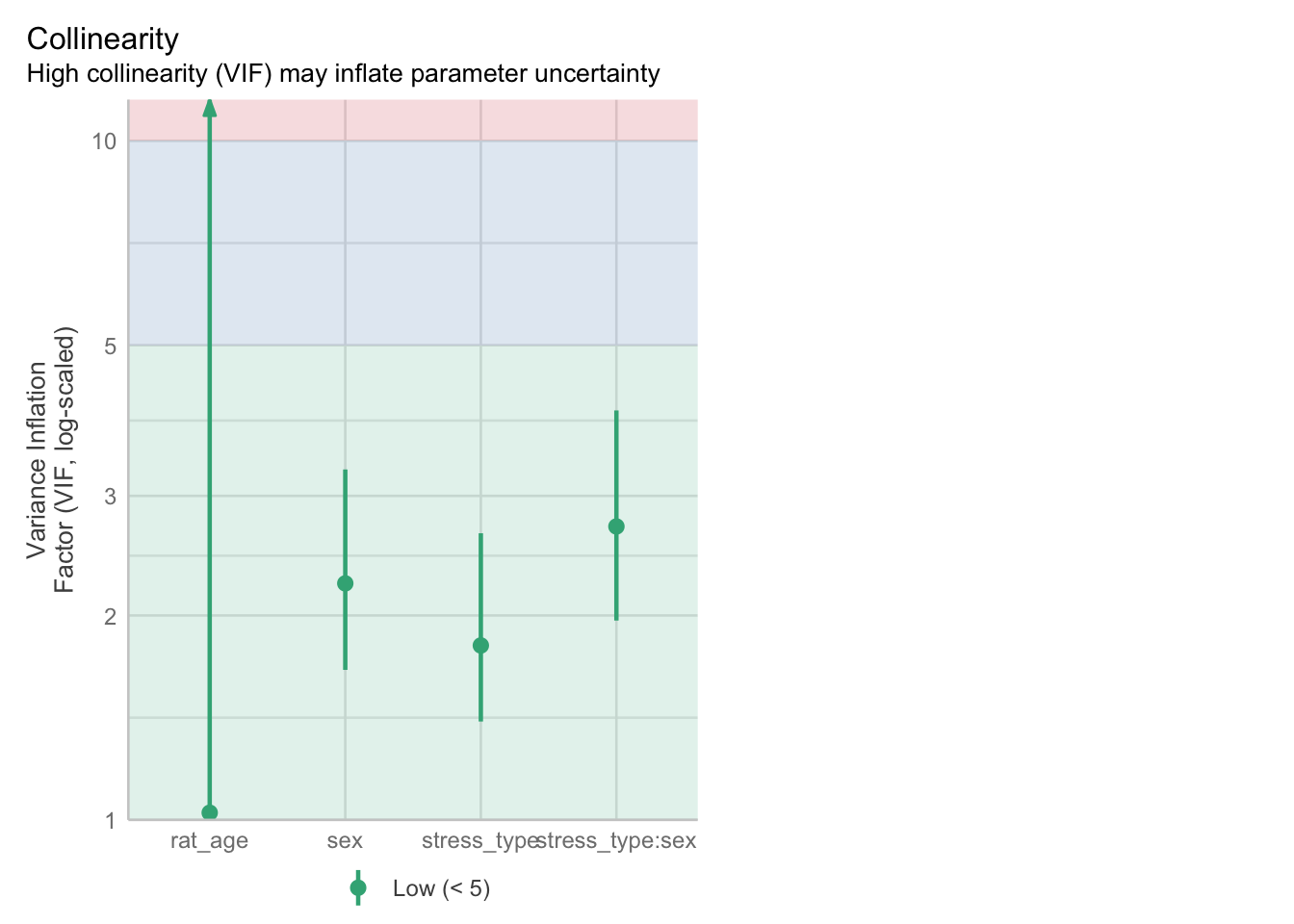

11.5.2 Lack of collinearity

The best way to assess whether we have collinearity is to look at something called the variance inflation factor (VIF).

When calculating VIF for a model, a separate VIF value will be generated for each predictor. VIF >5 is worth an eyebrow raise; VIF >10 definitely needs some follow-up; and VIF >20 suggests a really strong correlation that is definitely problematic.

check_collinearity(glm_dia)Model has interaction terms. VIFs might be inflated.

Try to center the variables used for the interaction, or check

multicollinearity among predictors of a model without interaction terms.# Check for Multicollinearity

High Correlation

Term VIF VIF 95% CI adj. VIF Tolerance Tolerance 95% CI

glucose 37.99 [32.97, 43.80] 6.16 0.03 [0.02, 0.03]

diastolic 24.24 [21.06, 27.92] 4.92 0.04 [0.04, 0.05]

glucose:diastolic 69.45 [60.21, 80.14] 8.33 0.01 [0.01, 0.02]We can also visualise the VIFs, if we prefer, with the VIF plot in check_model:

The statsmodels package contains a function for calculating VIF.

It uses the original data, rather than the model, to do this. This means you have to manually exclude the response variable, and then use the dmatrix function from patsy to create the matrix that can be used to calculate the VIF.

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

from patsy import dmatrix

# Drop the response variable

X = diabetes_py.drop(columns='test_result')

# Create design matrix based on model formula

X = dmatrix("glucose * diastolic", data=diabetes_py, return_type='dataframe')

# Calculate VIF for each feature

vif_data = pd.DataFrame()

vif_data['feature'] = X.columns

vif_data['VIF'] = [variance_inflation_factor(X.values, i)

for i in range(X.shape[1])]

print(vif_data) feature VIF

0 Intercept 600.539179

1 glucose 36.879125

2 diastolic 17.407953

3 glucose:diastolic 63.987700There is definitely some collinearity going on in our model - these VIF values are way over 10.

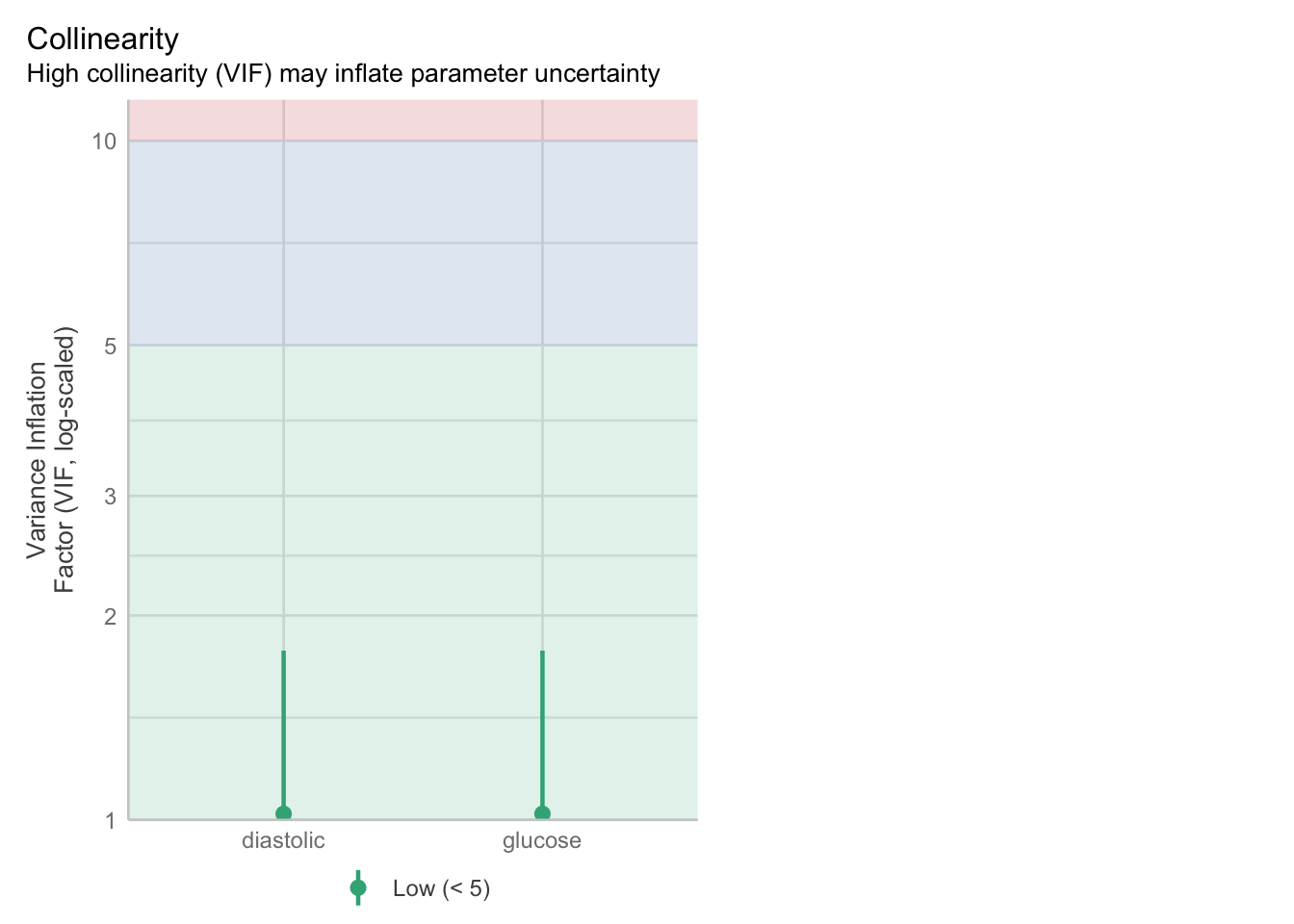

The most likely culprit for this is the interaction term - let’s see if we can improve things by dropping it:

glm_dia_add <- glm(test_result ~ glucose + diastolic,

family = "binomial",

data = diabetes)check_collinearity(glm_dia_add)# Check for Multicollinearity

Low Correlation

Term VIF VIF 95% CI adj. VIF Tolerance Tolerance 95% CI

glucose 1.02 [1.00, 1.78] 1.01 0.98 [0.56, 1.00]

diastolic 1.02 [1.00, 1.78] 1.01 0.98 [0.56, 1.00]check_model(glm_dia_add, check = "vif")Cannot simulate residuals for models of class `glm`. Please try

`check_model(..., residual_type = "normal")` instead.We will try again, this time without manually adding the interaction:

# 1. Drop the response variable

X = diabetes_py.drop(columns='test_result')

# 2. Add constant column for intercept

X = sm.add_constant(X)

# Calculate VIF for each feature

vif_data = pd.DataFrame()

vif_data['feature'] = X.columns

vif_data['VIF'] = [variance_inflation_factor(X.values, i)

for i in range(X.shape[1])]

print(vif_data) feature VIF

0 const 42.747425

1 glucose 1.052426

2 diastolic 1.052426Much better! This means that dropping the interaction term drastically improves the model.

Why does this matter? Well, if you want to make specific comments about the predictors, then collinearity is an issue, because dropping one of the predictors can cause large swings in the beta estimates. This is an issue if you try to have a meaningful model.

If all you care about is the overall accuracy of your model (the machine learning approach, where all we care about is maximum prediction) then collinearity becomes irrelevant, because the model and residuals don’t change due to collinearity.

11.6 Exercises

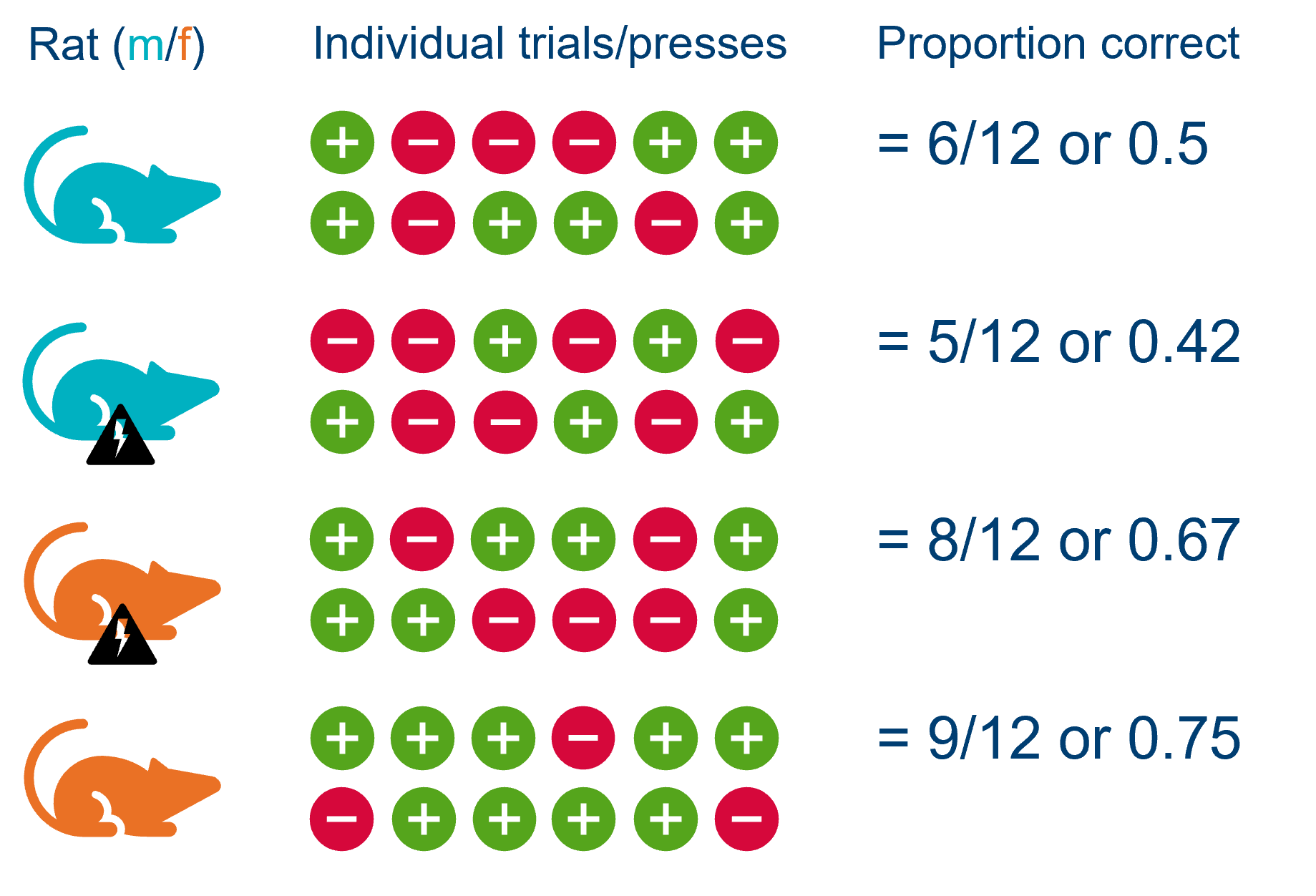

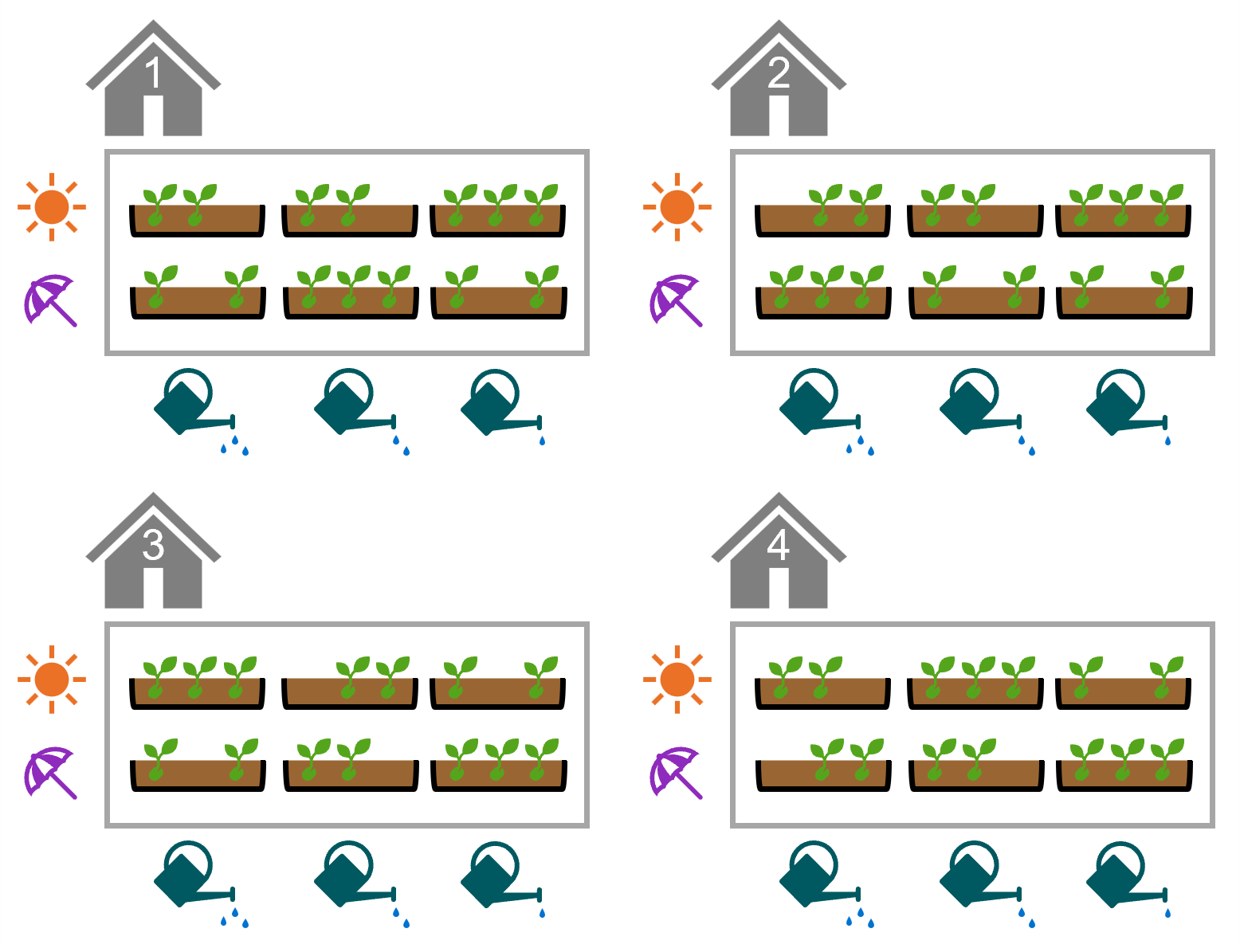

11.6.1 Revisiting rats and levers (again)

11.6.2 Seed germination

11.7 Summary

While generalised linear models make fewer assumptions than standard linear models, we do still expect certain things to be true about the model and our variables for GLMs to be valid.

- For a generalised linear model, we assume that we have chosen the correct link function, that our response variable follows a distribution from the exponential family, and that our data are independent

- We also want to check that there are no overly influential points, no collinearity, and that the dispersion parameter is close to 1

- To assess some of these assumptions/qualities, we have to rely on our understanding of our dataset

- For others, we can calculate metrics like Cook’s distance and variance inflation factor, or produce diagnostic plots